Three days ago Nick Staikos, the MP for Bentleigh, tweeted about a leaflet his constituents had received – at first glance it could be construed as coming from his office, rather than from Right to Life, and Mr. Staikos did not appreciate the confusion.

This will be a conscience vote, which means each parliamentarian will decide for themselves, ideally based on review of the facts, and reflection on the best interests of the people of Victoria. The seat of Bentleigh is one of a small handful of very marginal seats – over a month ago, the Australian Christian Lobby announced that it would be targeting these seats, and “vowed to derail the legislation and electorally punish MPs who end up supporting it”.

I have no problem with lobbying – those of us who want this legislation passed will also be calling on like-minded people to contact their MPs, will (as I have) write to papers and post things on social media. The key difference, as I see it, is that while the people I’m talking with are very careful to remain accurate, calm, and support our positions with facts, those who think differently appear to be a little less cavalier with the truth.

I was given a pamphlet that, as far as I can tell, differs from the one distributed in Mr. Staikos’s electorate only by the MP details. Let’s take a look at it.

I’ll set aside the fact that Right to Life have created a false binary (in which suicide prevention is antithetical to assisted dying) and note that, not only is this intentionally inflammatory, it falsely conflates suicide (the intentional ending of one’s viable life) with the inevitable death of a person in the end stages of a fatal disease, illness, or condition – in the case of the former, intervention can result in a healthy, happy life; in the latter, the only question is whether the end will be comfortable and on their terms, or tormented.

First of all, the “government-sanctioned suicide” will not be by doctors – except in rare cases, where patients are unable to do so because of physical or digestive reasons, the role of doctors is to assess, advise, refer as appropriate, educate, and (if indicated by the screening process and the patient’s unwavering intent) prescribe. The use of the phrase “sick and inform” is hard to read as anything but intentionally misleading – anyone accessing this legislation must be nearing or at the end of life, from a disease, illness, or condition, and have suffering that not able to be adequately managed, aand be competent, unwavering, and uncoerced.

The question “Is he trying to save healthcare dollars?” is an egregious allegation. While it’s true that people on average consume (for lack of a better word) more health resources in the last twelve months of life than at any other time, that is rarely because of palliative care; far more often it’s because death is fought, with ICU, investigations, expensive imaging, and surgery. I have spoken with doctors, Victoria’s Health Minister, other MP’s, palliative care and hospital administrators, and not once have any of these people mentioned money. More than that, I have cared for patients for over a quarter of a century, in Victoria’s public system; despite the pressure for beds, and KPI’s, and review meetings regarding length of stay, nobody has ever suggested cost as a reason for transferring a patient or changing their care. If the Premier were motivated by that, a) surely he would have brought this up as an option earlier, either pre-election or when he was health minister, and b) his position wouldn’t have changed following his witnessing the dying of his father.

Right to Life end the facing page with equal distortion. We already have world class patient care, improving palliative care resources, and nobody is killing other people. The line “the life you save may be your own” is ridiculous – even in Belgium, where some of the most liberal laws are in place, people are not at risk of being killed against their will. Oregon’s laws are unchanged in two decades, and Victoria’s Bill is even firmer – this is nothing but fearmongery.

Onwards.

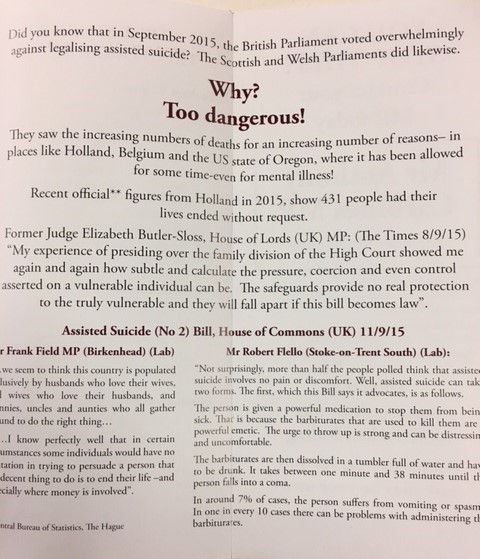

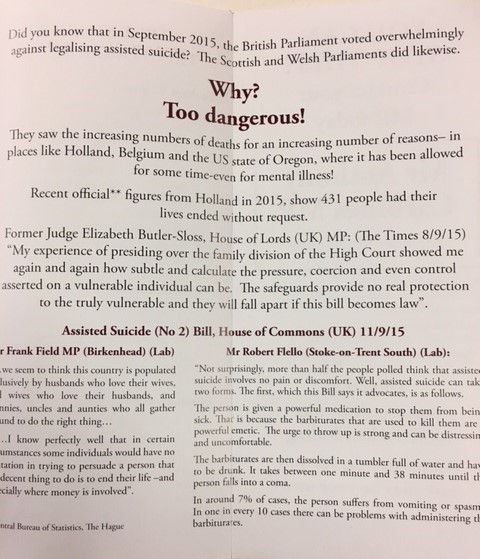

Apparently Right to Life are unaware that Britain comprises England, Scotland, and Wales…

It is true that, over time, utilization of these laws increases – as is the case with anything novel, from smart phones to laparoscopic surgery:

“If you legalize on the broad basis (that) the Dutch have, then this increase is what you would expect,” said Penney Lewis, co-director of the Centre of Medical Law and Ethics at King’s College London. “Doctors become more confident in practicing euthanasia and more patients will start asking for it,” she said. “Without a more restrictive system, like what you have in Oregon, you will naturally see an increase.” (source)

In the Netherlands, that increase is from 1.7% of all deaths in 1990 (before the introduction of legislation) to 4.5% in 2015; in Belgium

It is also true that both the Netherlands and Belgium have widened the parameters under which assisted dying may be provided, and that a person who has unbearable suffering without realistic likelihood of improvement meets the criteria, even if that suffering is psychological rather than physical. In the table below, “Underlying illnesses of Dutch assisted dying cases (proportion of all deaths)” (source), those patients are represented in bright blue, and account for some 3% of all assisted deaths in 2015. Cancer, which is the cause of almost a third of all deaths in the Netherlands, also accounts for the overwhelming majority of assisted deaths.

It is utterly untrue that the Oregonian law allows people accessed to assisted dying because they have a mental illness. A person must be:

1) 18 years of age or older,

2) a resident of Oregon,

3) capable of making and communicating health care decisions for him/herself, and

4) diagnosed with a terminal illness that will lead to death within six (6) months. (emphasis added, source).

Absolutely nothing there about mental illness being a reason to access the Act though, as here, having or having had a mental illness does not prevent someone applying, provided they are clinically competent.

Ms. Tighe’s pamphlet also refers to 431 people in the Netherlands whose lives were ended without specific request, and that appears to be accurate – on CBS’s statistical summary dated May 24 of this year, the breakdown of 7, 254 assisted deaths (of a total of 147,134 for the year) includes 431 titled “Levensbeëindigend hand. zonder verzoek” (or ‘assisted, end-of-life, without request’). That’s 0.059% of the 4.9% of Dutch deaths that are assisted, and that figure doesn’t tell us anything about the cases, or prior directives, and as 350 of those cases were patients aged 65 and over (201 of which were over 80), it is fair to assume many involved end-stage dementia.

This is certainly not ideal, but it’s also not applicable to the Victorian situation, where competency is an integral component of the process. It’s a pleasant to change to find a verifiable, accurate fact in this pamphlet, albeit one I suspect is also the worst Ms. Tighe’s organisation was able to find.

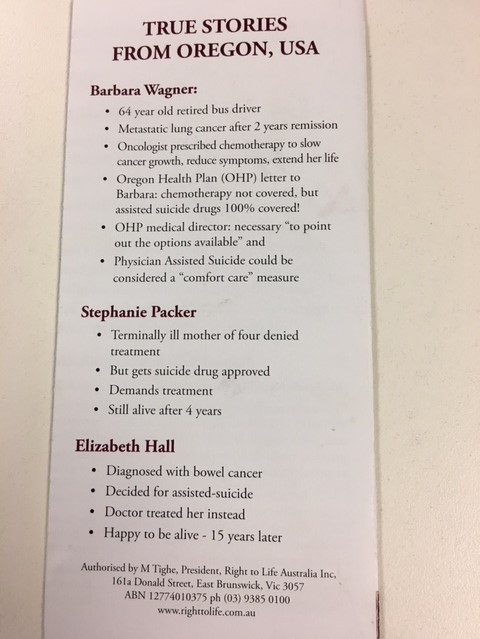

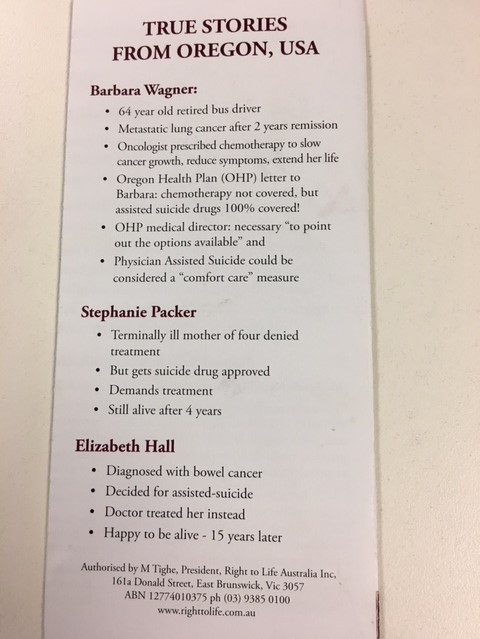

Speaking of verifiable facts, when we turn the page we find three cautionary cases from Oregon of women who were either forced into this option, or avoided it and lived happy lives.

As there are no citations, I have had to search for these stories myself.

Ms. Wagner’s case was publicised in 2008 when, after several years of treatment with first and second line chemotherapy, her insurance company refused to pay for an experimental drug that would potentially extend her life from four to six months, as Tarceva did not meet their requirement of 5% survival at 5 years. Indeed, at the time the drug made no significant improvement for 92% of patients, though it did induce rashes, diarrhea, and other unpleasant side effects in 19% of people taking it. Instead they were only prepared to cover palliative and comfort care, which included (but was not restricted to) assisted dying. After the media storm, the drug manufacturer agreed to cover the futile treatment; there are reports that Ms, Wagner died shortly thereafter.

Ms. Packer lives in California, and was anti-assisted dying well before any discussion about treatment funding. She was diagnosed with scleroderma, an autoimmune disease that causes scarring of body tissues, which was treated with chemotherapy; after three years, she entered negotiations with her insurer who, after five months, agreed to cover an alternative treatment, then changed their mind.

Packer then called her insurance company to find out why it wasn’t covered, and in none of the articles, Packer actually tells us why. You’d think that information would be useful in a news article about coverage denial. Instead, while on the phone with her insurer, she asked them if they cover the assisted suicide drugs and they said yes. The insurance company did not “offer to pay for her to kill herself.” (source)

Even if these cases had happened as described, they would not be reason to vote against the Victorian bill – Australia has universal health coverage, the overwhelming majority of people who need end-stage support use public facilities, and our private health insurance is voluntary, and paid by individuals – any company that instituted an policy that disallowed proven treatments with genuine outcomes would be abandoned by members in droves.

Death With Dignity have discussions about these and similar cases presented by groups like Right to Life, though Elizabeth Hall is not one of them. Google searches for “Elizabeth Hall” + “bowel cancer” + “assisted dying” came up with no relevant hits, and searches substituting “assisted suicide” and then “euthanasia” were similarly fruitless. There are insufficient details related on the pamphlet to know if the mysterious Ms. Hall would have met Oregon’s requirement of a six-month (or less) prognosis, but the number of people with end-stage bowel cancer who survive more than five years (let alone 15+) is very low.

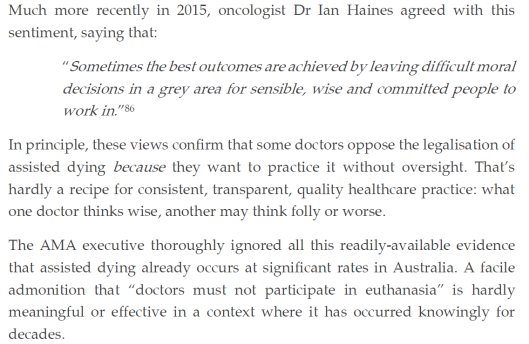

What’s my take home message about these pamphlets? They certainly don’t seem to be created with education in mind, or even an argument against assisted dying based on any kind of coherent platform. Instead they have been written to heighten fear and apprehension, with deliberate skewing of the facts, and omission of vital information. If your argument can’t stand in the light, if it must be cloaked in emotion and distortion, then it isn’t robust, it isn’t valid, and it isn’t worth listening to.

Francis, p. 39

Francis, p. 39 (

(